White Veganism, Black Veganism: A Critique

– Christopher Sebastian

A lot of digital ink has been spilled in online spaces over the past few years about white veganism versus Black veganism. There is no universally agreed-upon definition of white veganism, but a 30-second collaboration video by author and influencer Blair Imani featuring a compilation of diverse voices within the vegan movement encapsulates the spirit of the issue, “When you fail to account for white supremacy in veganism, you get White veganism.”

As a response to this, many Black and brown activists online have popularized the phrase Black veganism in opposition to white veganism. There’s nothing wrong with this, but it comes with several limitations.

First, setting up Black veganism as an answer to white veganism can be seen as reactionary in that it unnecessarily centers whiteness. Plus, many people use white veganism as a proxy to air their grievances about veganism, which is often a way of disguising their contempt for animals and animal liberation.

For example, popular disability advocate Imani Barbarin sparked a firestorm on Twitter when she wrote an extensive critique of white veganism. In her video, she astutely lays out all the problems endemic to White veganism, but she introduces her post with the following text.

“I woke up and chose beef.”

[imani is responding to the comment @/ vegandesign : “how people (rightfully) stand against injustice and oppression but ok w cows being forcibly impregnated & having their day old newborns stolen?”]

But this response shrewdly avoids answering the actual question, which was about the systemic sexual, reproductive, and emotional violence inflicted on bovine animals. To the contrary, she mocks it by joking that she “woke up and chose beef.” Even if she does not believe the question itself is asked in good faith, responding by objectifying the cow is itself an act of violence that is compounded by allowing the comments and replies to perpetuate endless streams of anti-animal bigotry completely unchecked. In this case, white veganism became the vehicle those social media critics used to discredit veganism altogether.

When challenged by Black pro-animal voices about our collective obligations toward other animals, many of those voices were either met with silence or accused of being colonized by white thought. So white or not, the outcome is that people have learned that it is easy to avoid accountability for animal violence by treating any meaningful discussion of species solidarity as rooted in white veganism.

Of course, it’s easy to see why it’s attractive to bucket veganism into white and Black identities. After all, feminism followed a similar trajectory with the explosion of rich Black feminist thought that followed the constraints of white feminism. However, most people today would probably agree that feminism is distinct from white feminism and that feminism itself is not to blame for the shortcomings of white women.

Another key difference here is that Black feminism as we understand it does not seek to marginalize or exclude. In contrast, some Black vegans seek to both sideline animals and marginalize other humans.

Take the social media accounts of That Vegan Melanin. With over 61k followers on Facebook and 35k followers on Instagram at the time of this writing, the accounts share an impressive amount of information about plant-based eating. But they’re also a hotbed of sexism, homophobia, and disinformation.

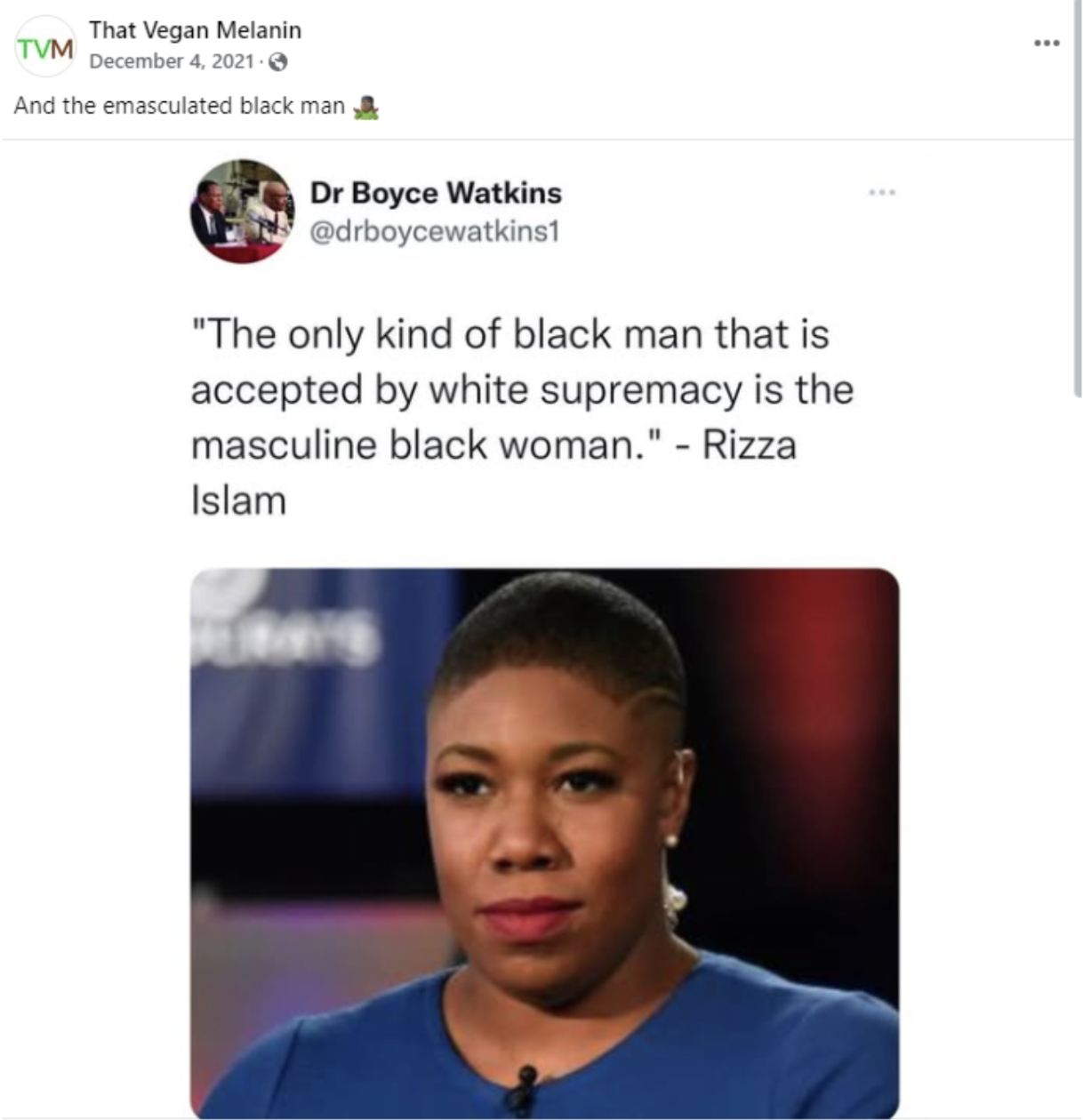

Here’s a Facebook post that actually combines sexism and homophobia for good measure. It’s a screenshot of a tweet featuring a photograph of U.S. political commentator and democratic strategist Symone Sanders. The text over her is a quote purported to be from Rizza Islam saying, “The only kind of black man that is accepted by white supremacy is the masculine black woman.”

It implies that Black female strength is itself anti-Black and frames Black female leadership as white. The choice of Sanders also comes across as deliberate because the masculinization of Black women with short hair and strong features can be regarded as undesirable to the Black male gaze. That Vegan Melanin compounds this with homophobia by including his own caption that adds “and the emasculated black man.” Is this the Black veganism that is meant to liberate?

Here’s another post glorifying both grind culture and clean eating. It’s a photo of a Black man with dreadlocks surrounded by whole plant foods under the words “Kings eat clean.”

Again, That Vegan Melanin adds his own caption that states

“Health equals wealth" is a true statement. When you take care of your spiritual, physical and mental health, finding and focusing on your purpose will be much easier. Men who are creators and inventors know they have to put in a lot of hours in order to reach their goals. I believe Men who wants to find success should a[t] least put in 60 to 80 hour work weeks with 6 hour minimum of sleep…

Mathematically, he is advocating people to work the equivalent of two full-time jobs in a world where low-income people are already overworked and undercompensated. Plus, he marries this to the myth of clean eating. If part of Imani Barbarin’s critique of White veganism is that it is rooted in fatphobia, diet culture and disordered eating that is covered up as a lifestyle (see #9 on her list), then is this presentation of veganism…White?

These are the murky complications that arise when ascribing race-based qualifiers to veganism. Is it accurate to pour all negative connotations of veganism into white and frame all politically active and social justice-minded veganism as inherently Black? Being Black alone does not automatically make veganism more liberatory by sole virtue of its Blackness.

Another powerhouse of Black vegan social media is TheBlackVeganTube, an Instagram account that has over 32k followers. Again, that’s a lot of users consuming Black vegan content. But that content contains an alarming amount of pseudoscience and wellness culture. The page sells everything from dietary cures for cancer to an assortment of treatments that reveal a bewildering obsession with herpes (no seriously, there are a LOT of posts about herpes).

Given the current and historical maltreatment of Black and Brown people within the institution of Western medicine, it’s understandable that minoritized people would seek alternative treatments and naturopathy for health. And there is a tremendous amount of Indigenous wisdom to be reclaimed from communities that western medicine has ignored. But it is irresponsible and dangerous when pages confuse or conflate ancient and Indigenous knowledge with sorcery that can get people killed. Likewise, there is no evidence that a plant-based diet is inherently better or worse than any other diet because food being of plant origin does not necessarily connote health.

But do these claims not represent toxic diet culture? Is it not rooted in ableism and exploitation of people victimized by the failures of the medical and scientific establishments? Because yet again, the claimants are Black.

For what it’s worth, in 30 days of content, not one post from TheBlackVeganTube or That Vegan Melanin (on either of his platforms) directly centers the liberation of other animals or meaningfully addresses animal justice. Instead, they focus almost entirely on plant-based eating and sometimes Black joy mixed in with varying degrees of low-level bigotry and disinformation. There is almost no engagement with veganism as it confronts anti-animal bigotry.

While some people within the community may think of this observation as gatekeeping, the distinction between veganism as an ideology as something separate from a plant-based diet is an important one for people who reject animal exploitation because that exploitation goes far beyond the use of animals for food. Here is a photograph of celebrity vegan Erykah Badu modeling a mink coat for Marc Kaufman furs. According to Animal Ethics, that’s anywhere between 50 and 60 animals for a single garment, none of whom were eaten.

Nonetheless, some Black scholars reject the notion that veganism should be a moral imperative that highlights animal liberation. In a powerful essay, Professor Lisa Betty of Fordham University writes that “moving forward as an anti-oppressive social justice movement means veganism must place emphasis on access, not choice and morality.”

To be clear, access to plant-based foods must absolutely be addressed as a matter of food justice and food insecurity—adjacent movements that the vegan movement should be aligned with. But presenting access and morality as mutually exclusive is unnecessary, and conflating food justice with veganism unintentionally reduces veganism again to a diet that has no more political utility than keto or paleo. Health is relative, and anyone who eats any of those fad diets can claim it.

Betty also risks erasing the legacy of other Black revolutionaries that she cites herself in the same essay. The Philadelphia MOVE organization was very explicit that they operated in solidarity with animals who live under, in Janine Africa’s words, “any form of slavery.”

Furthermore, emerging research into vegan advocacy indicates that reducing the focus on morality could produce negative outcomes. According to a study from Dr. Trent Grassian in the UK, participants in vegan campaigns who are motivated by animal protection are more strongly linked to larger reductions and higher levels of successful reduction and elimination than all other motivator categories, including health and environment.

Grassian’s study does not specifically outline the demographics for Black participants. But pair this with other social science that indicates wealthy people are less likely than poor ones, in lab settings at least, to relate to the suffering of others. Given that Black and brown people are disproportionately impacted by poverty, it’s possible that minimizing attention to interspecies solidarity can hurt more than it can help. It’s too early to say for sure, but the point is that it’s complicated.

It is a harmful and a historical myth to presume that white people are more empathetic than Black and brown people. And given the rising chorus of Black animal advocates who are unapologetically vocal in their support of animal liberation on social media, one that is quickly becoming disproven. Digital activists Yvette Baker (she/her) and Zaynab Shahar (they/them) are two such examples who provide especially thoughtful and provocative perspectives.

Veganism is not in crisis. As a movement, veganism is experiencing growing pains, and they’re not particularly new. A paper by Dr. Corey Wrenn documented this as early as 2018. Factionalism within movements occurs, but it’s not only normal, it’s healthy. A movement devoid of self-reflection and critique is dead. That’s not a crisis, it’s growth.